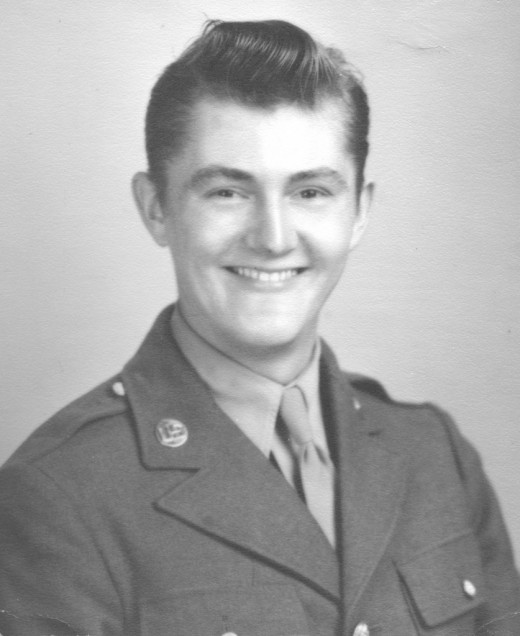

On December 16, 2014 will mark the 70th Anniversary of one of the largest battles ever fought in United States history: The Battle of the Bulge. Nearly 20,000 U.S. soldiers would die in this battle that would last for over a month. It was on December 16th, 1944, my father, Henry T. Bielicki, was wounded in the Hurtgen Forest forever changing his life and mine.

He is now passed away. I remember my dad talking to other veterans who stayed at our little hotel/restaurant on Federal Highway back in the 1960’s, also known as Jake’s Restaurant in the 1980’s, now the refurbishing Straticon Building. Unlike other veterans who remained silent about the war, my dad would talk freely about his experiences. People called him, Henry, and he did not mind us children calling him “Henry” either.

I firmly believe his stories influenced me to become an American History teacher—23 years at MCHS. Dad’s sense of wonder, travel and love for the ocean transcended into us kids. His most important gift, though, was life itself, of staying alive. His large scar in his lower back will always be embellished in my mind. Below is an oral record of what my dad said about those times.

The bomb landed near my dad. Shrapnel went into his lower back and he remembers “doing a somersault.” Henry was given the “last rites,” as the doctor was about to operate. Luckily, that doctor decided not to as the shrapnel was too close to his spine.

For the next sixty years a small monthly check, about $147 dollars, would always come in the mail. Then, too, the Veterans Hospitals always took great care of my father. He still had shrapnel in his back when he passed away.

My dad was wounded on the first day of the Battle of the Bulge and the last day of the Battle of Hurtgen Forrest, December 16th, 1944. I still have his official “dark issued paper” to prove it. He was with the Army 83rd Infantry Division, known as the Thunderbolt Division. Henry was like many young Americans at that time: he was drafted. The military actually came to his house in Philadelphia to pick him up.

My dad landed in Normandy twelve days after the initial D-Day invasion. Thousands died on that fateful day of June 6th, 1944. Henry remembered seeing all these “black bodies” piled high. Henry made a comment to a fellow soldier, “that he didn’t know that colored men were fighting.” I do not know if any expletives were made, but someone told my dad that “those bodies were decomposing white soldiers.”

Henry was involved in the fighting through the murderous hedgerows of Normandy. He recalled that a German pilot was shot down and there was not much left of the pilot after everyone shot at him.

A German Panzer unit surprised his unit and he said “many just put their hands up.” My dad and a buddy jumped into a swamp and survived. With Google, I actually have found references about that Panzer Division in Normandy.

My dad would talk about seeing a German “buzz bomb” flying around Trier. He learned later it was a Messerschmitt 262’s flying in combat. Those planes were the first operational jet-fighter aircraft ever made.

“Every day I felt I was going to die,” I recall my dad saying. There was one episode when a German soldier came around a tree and confronted my dad and his buddy. Luckily, the German was using a single bolt action rifle. The German shot my dad’s buddy who was carrying a machine gun. My dad had his M1 carbine on semi-automatic. Eight bullets were quickly fired. That German and my dad’s buddy were dead.

Henry was in the front lines for seven months. He was used several times as a lead scout. The Germans were smart allowing the lead scout to pass and firing on the rest—like “a flock of turkeys” quoting the Sergeant York movie about W.W.I.. There was one time my dad asked not to take that lead role. His sergeant volunteered and was killed that day.

There were just a few good times particularly when his outfit walked into a village that produced champagne. Where and when this incident took place is still a mystery. Henry would smile as he told the story to fellow veterans.

The 83rd managed to make it into western part of Germany. In an unknown village my dad snatched a Nazi flag off of a postal flag-pole. I still have that flag and it became a show-and-tell piece at school for many years. My dad’s stories became real after seeing that flag riddled with holes and his dark stained blood.

Henry was on guard duty on an open road when an American soldier in a white tee-shirt came up to him with a German prisoner. They asked where the commanding post was located. My dad pointed down the road. “I was a dope,” my dad stated as he did not realize this American soldier was probably a Greif commando—Germans disguised as American soldiers who spoke very good English. About thirty minutes later, bombs started to explode around him and that is when he was injured.

My dad was sent to Paris to recuperate. Later he was sent to White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia for his final hospital stay at the Ashford General Hospital, formerly known as The Greenbrier and nicknamed “The Shangri-La for Wounded Soldiers.”

After the war, he used the Veterans benefits and graduated from the Philadelphia Museum School of Art. He became a free-lance greeting card artist moving to Stuart in 1960. Henry sold water-color paintings from the hotel’s restaurant along US1. Whimsically, I claim Henry was the original “white” Florida Highwaymen painter from those times. In March 2005, he passed away down at the West Palm Beach Veterans hospital.

Dad did not really care too much about his flag or his helmet and we were allowed to play with his war relics in our big yard by Frazier Creek. We would put the flag on a long cane pole and play our children war games. One day the Stuart Police came by and asked us not to show that flag again. It has been in a special red bin ever since—except for the show-and-tell with students.

Author: Marty Bielicki lives in Jensen Beach and is now retired after 37 years teaching American History and Dean at MCHS.